A Review by James Tipton:

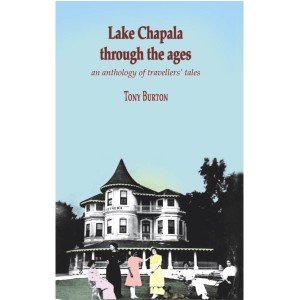

Lake Chapala through the Ages: an anthology of travellers’ tales

Edited with Historical Notes by Tony Burton

Sombrero Books, B.C., Canada. 215 pages $24.95 (Canadian)

Tony Burton’s passion is Mexico, and particularly Western Mexico. Most readers of Mexico Connect find his many articles on Mexico to be both fascinating and useful, articles with titles like “Guayabitos — the Family Vacation Spot,” or the four-part series, “Can Mexico’s Largest Lake Be Saved,” or “Butterflies by the Million: The Monarchs of Michocán.” Burton currently puts together “Did You Know? Facts About Mexico,” a monthly Mexconnect feature, offering answers to such questions as: “Did you know blacks outnumbered Spaniards in Mexico until after 1810?” or “Did you know the oldest winery in the Americas is in Parras de la Fuente” or “Did you know the birth control pill came from Mexican yams?”

This man has a knack for searching out and then writing well about interesting places, people and events. Because I like to read what Tony Burton writes, Lake Chapala through the ages is one of those books I would buy sight unseen.

Many readers own his book Western Mexico—A Traveller’s Treasury (now in its third edition in English with a new edition well under way), which has taken us to off-the-beaten-path destinations. A geographer, Burton has also created the definitive street maps of the Lake Chapala area, maps that have been copied by others but which are original with Burton: Lake Chapala Maps — 2008. Obviously Burton is no stranger to our shores here at Lake Chapala.

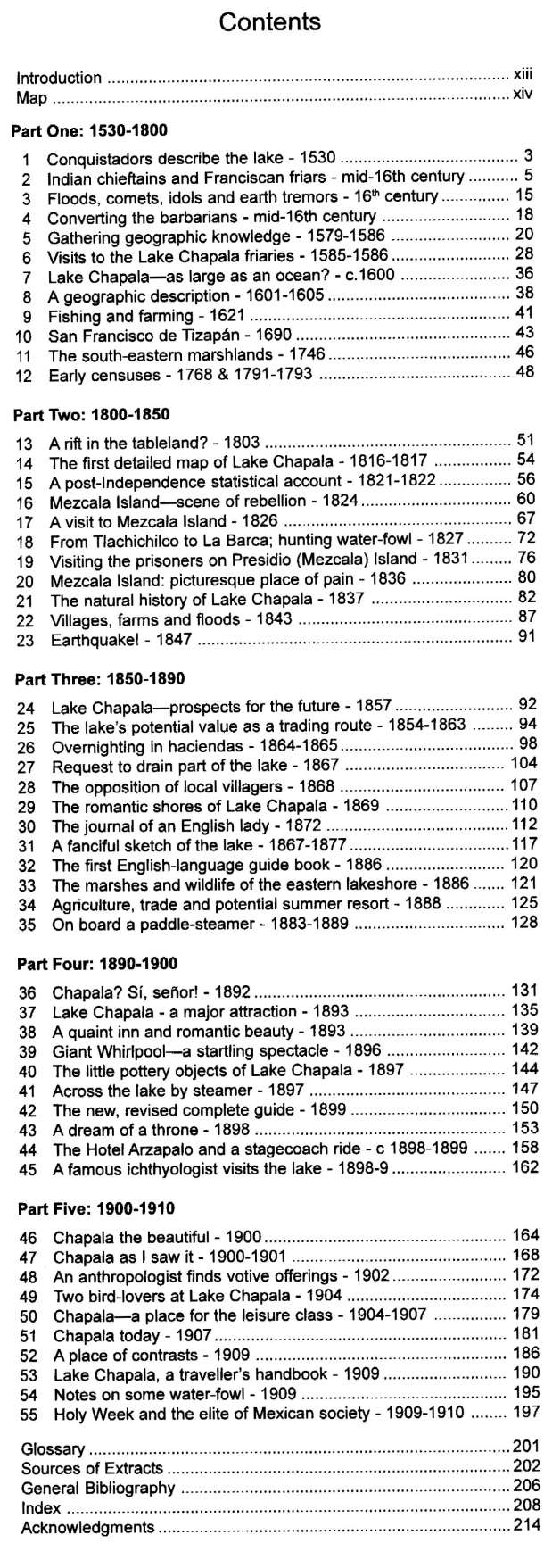

Lake Chapala through the ages is “a collection of extracts from more than fifty original sources.” In the Introduction, Burton tells us his book “includes extracts from every published book that could be located which makes more than a passing mention of Lake Chapala, and which was written (originally) prior to 1910. Most are first hand accounts.”

Burton selected 1910 as the cut-off because “that marks the end of Chapala’s first tourist boom.” “Later that year the Mexican Revolution erupted. Mexico, including the Lake Chapala region, was thrown into chaos for more than a decade.”

Lake Chapala through the ages presents, then, historical accounts, beginning in 1530 when the first conquistador wrote about seeing the lake — and also the town: ”The scout, going over the mountains found himself in a village called Chapala and in other places whose names were not known at that time….” Lake Chapala through the ages ends with a piece about “Holy week and the elite of Mexican society 1909-1910,” in which we discover:

“Chapala, the most frequented settlement of the lake of the same name, serves as a meeting place during Holy Week for the elite of Mexican society. Elegant villas line the edge of the lake, surrounded by colorful gardens, created at great expense on the rocky soil of the beach. One of the prettiest, “El Manglar”, belongs to Mr. Elizaga, the brother-in-law of ex-President Díaz, who gives, in this enchanting setting, splendid Mexican fiestas, where nothing is lacking: cock fights, balls and joyous dinners.”

In addition to the excerpts, Burton himself provides many historical notes. We learn that Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec capital in August of 1521, but only two years later, in 1523, two “well-placed brothers, cousins of Hernán Cortés,” were given the encomienda (the right to collect tributes and labor from Indians)” for a vast area that included the shores of Lake Chapala. The Spanish subjugation of the Indians in this area was “a relatively peaceful process, which enabled many indigenous customs to survive largely unchanged into much more recent times.”

Most of the early accounts were written by Franciscan friars. The Franciscans “saw the New World as an opportunity, not only to convert the pagan masses of native Indians to Christianity, but also to put their idealistic ideas of utopia society into practice, and demonstrate that natives and Europeans could live in peaceful and productive co-existence.”

Some of the excerpts are about those early relationships with the Indians: “Converting the barbarians” (mid-16th century),” but others are about geographical details — “Gathering geographic knowledge” (1579-1585) or “Lake Chapala… as large as an ocean?” (1600c). Still others are about a new paradise, filled with abundance, and with fascinating new fruits and vegetables: “Some roots that are called xicamas grow there, shaped like, and almost the same color as, round turnips, without any roots hairs, so thick that each one weighs at least thee pounds…. It is a very delicious fresh fruit, marvelous medicine for thirst, especially in hot weather and in hot lands.” (from “Visits to the Lake Chapala friaries” 1585-1586).

We discover, through Burton’s notes, that Domingo Lázaro de Arregui (Fishing and farming” 1621) made the earliest known historical reference to the making and consumption of tequila: roasting the roots and bases of agave plants then “by pressing these parts, thus roasted, they extract a must from which they distill a wine clearer than water and stronger than rum.”

In earlier censuses taken by the Spaniards (“Early censuses 1768 and 1791-1793”) we discover that Chapala had 123 Spaniards, 451 Indians, 37 mulattos and 671 castes, figures that were particularly interesting to me because the castes (those of more mixed parentage than mestizos or mulattos) now significantly outnumber the Spaniards and Indians combined.

Throughout Lake Chapala through the ages, Burton selects highly varied material that does not bore us with the weight of history and ponderous prose but instead actually delights us and even makes us long for more. Many passages are actually charming, and the historical notes provided by Burton are themselves illuminating and pleasurable.

In his notes to “Mezcala Island — scene of rebellion” (1824), Burton tells us the Italian author, Giacomo Costantino Beltrami, was an “incurable romantic and inveterate roamer,” who among other accomplishments discovered the northern source of the Mississippi River. Beltrami describes his visit to Mezcala Island, which by 1824 was being used as a penitentiary, where the convicts, Beltrami notes, “are less harshly treated than in the penitentiaries of our World [Europe], the dictator of civilization.” Shortly after he visits “Oxotopec, ten milles from Axixis,” Beltrami, with his youthful eye, records that it is “the largest village of all those around the lake,” but that “it has nothing worth noting except for the pretty niece of the curate….”

Even as we move toward more recent times, when there are attempts to accurately determine the dimensions of Lake Chapala, we still high imaginative descriptions of Lake Chapala. Felix Leopold Oswald in “A fanciful sketch of Lake Chapala” (1867-1877) announces Lake Chapala is “ten times as large as all the lakes of Northern Italy taken together, and four times larger than the entire canton of Geneva, — contains different islands whose surface area exceeds that of the Isle of Wight, and one island with two secondary lakes as big as Loch Lomond and Loch Katrine!” [The Isle of Wight, incidentally, is 23 x 13 miles, almost as large as Lake Chapala. Loch Lomond, Scotland’s largest lake, is 24 x 5 miles.]

By the early 1900s, tourism comes into sharper focus. One early and popular traveller’s guide, Lake Chapala, a travellers’ handbook (1909) by Thomas Philip Terry lists rooms available in Chapala, e.g. Hotel Arzopala, “facing the lake,” at $2.50 to $5 American Plan. In his note to this excerpt, Burton tells us that D. H. Lawrence, because of this handbook, was convinced to visit the lake; and of course Lawrence ultimately moved to Chapala in the mid-twenties and this is where he wrote The Plumed Serpent.

Those of us who live here, full time or part time, or who simply visit here have been relieved that the lirio, the noxious water hyacinth, seems at least for the time being to be well under control. I, like others, thought that the lirio problem originated only a few decades ago, but Burton tells us that it was introduced around the turn of the last century, and that by 1907, articles were being published about “the invasion of the terrible aquatic lirio,” which in some places “has completely blocked some docks, and in others it has appeared in such large masses that the Indians have been forced to suppress their trips, damaging trade, scared that they will be caught up in the wave of green.”

And so, there is something for everybody in Tony Burton’s, Lake Chapala through the ages. Whether you are fascinated by the early history of the place where you now live or visit (or would like to visit), or whether you interested in early accounts of the natural history of the region, or of the lake itself, or whether you are fascinated by those votive objects found on the bottom of the lake, or whether you simply want to connect yourself more deeply to the place you now call home (or that is “home” in your imagination), this book is for you.

I think Lake Chapala through the ages is terrific. Buy it!